A History of Christian Missions: Book Review (III)

Continued from Parts I & II of the Book Review:

Chapter 10: The Heyday of Colonialism

Resuming the narrative of the “Great Century” of Christian missions, Neill opens the chapter by pointing to the pivotal nature of the year 1858. For one thing, an “extraordinary constellation of genius, talent, and power . . . existed in the middle of the nineteenth century,” coupled with “the confidence with which the European world was animated, both in Church and State, at the opening of the period of its greatest influence. . . . Peace reigned almost unbroken for more than half a century [thereafter]. The whole world was open to Western commerce and exploitation” because of the West’s military superiority. “The day of Europe had come” (272).

Neill observes, or opines, that the “missionary enterprise of the Churches is always in a measure a reflection of their vigour, of their wealth, and of that power of conviction which finds its expression in self-sacrifice and a willingness for adventurous service” (274).

He then notes five major events that marked a turning-point in history and in Christian missions: First, the “acceptance of the British people, through its government, of responsibility for rule and administration in India,” ending the reign of the East India Company. British rule brought both peace and religious freedom to the sub-continent for the first time, opening the door to Christian missions (274).

Second, “the second war of the European powers with China had ended in 1858 with a series of treaties between China and the several European nations, [which gave] permission to foreigners to travel in the interior beyond the Treaty Ports . . . [and] guaranteed toleration of Christianity and protection of Christians in the practice of their faith” (275). These “unequal treaties,” as the Chinese called them with resentment, opened the way for missionaries to spread the gospel throughout the Chinese empire.

Third, the “Second Evangelical Awakening, starting among laymen in America with an intensity for individual and corporate prayer, crossed the Atlantic, and woke revival in many areas. . . . The new spiritual life into which many Christians entered found expression in a sense of responsibility for personal witness to Christ and for missionary service” (275).

Fourth, in 1858 “the first foreign missionary in modern times, a Roman Catholic priest, entered Japan,” to be followed eventually by Protestant missionaries from America and elsewhere (273).

Fifth, in 1857, David Livingston published his Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. The Christian world was convinced that the time had come to “resume evangelistic efforts in Africa” (275).

Neill goes on to tell the thrilling stories of foreign missionary endeavors in Japan, China, Korea, Southeast Asia, the South Pacific, India, the Middle and Near East, Africa, Latin America, and North America. He combines remarkable conciseness with enough details about people, events, and organizations to retain our interest and provide deep insight into complicated histories.

As before, I will focus on China.

“In China, the new-found liberty granted by the treaties encouraged rapid increase in Protestant work. Many new societies entered in. . . . A revolutionary change in the situation was brought about, as is so often the case, by the faith and conviction of one man,” Hudson Taylor (282). Neill concisely relates the story of Taylor’s early years and the founding of the China Inland Mission, whose principles differed from those currently used by other societies:

(1) “The mission was to be interdenominational. Conservative in its theology, it would accept as missionaries any convinced Christian, of whatever denomination, if they could sign its simple doctrinal declaration.”

(2) Those with little formal education could join the CIM. “It was good that one society was prepared to keep this door open; and cases were not lacking in which those who started with very little education grew to be notable scholars and sinologists” (283).

(3) “The direction of the mission would be in China, not in England – a change of far-reaching importance. And the director would have full authority to direct.” Neill is quick to point out that this principle did not come from Taylor’s arrogance, but from practical experience.

(4) “Missionaries would wear Chinese dress, and as far as possible identify themselves with the Chinese people.”

(5) “The primary aim of the mission was always to be widespread evangelism. The shepherding of Churches and education could be undertaken, but not to such an extent as to hide or hinder the one central and commanding purpose” (283).

Despite major difficulties and setbacks, “almost from the start his success was sensational” (283). Within thirty years, the CIM had missionaries in almost all the provinces of China. In addition to many members from humble backgrounds, the CIM attracted a few men from the educated classes, like the famous Cambridge Seven. Likewise, though most converts were ordinary folk, some were scholars, like Pastor Hsi. “In nothing was Taylor’s wisdom more remarkably seen than in his capacity to hold together his motley crew and to use their various gifts to the best advantage” (284).[1]

“The greatest service rendered by the CIM was that it demonstrated the possibility of residence in every corner of China” (284). Neill emphasizes the great reach of the CIM, perhaps reflecting the unfounded criticism of many that its work was too superficial. In fact, Taylor’s policy called for itinerant preaching that led to settled work in major cities and towns.

Neill rightly contrasts the approach of the CIM with that of Timothy Richard and others like him. Richard hoped to reach the masses of Chinese through concentration upon a few people. Recent scholarship has shown, however, that the goal of Richard’s wide diffusion of secular knowledge among the educated elite was not the conversion of this class, but the removal of prejudice and superstition which would, he hoped, reduce barriers to the gospel.[2] Soon other missionaries joined in the campaign to provide higher education to Chinese young people. Colleges and universities founded by foreign missions proliferated, mostly spearheaded by Americans. (Neill does not say this, but these institutions did not produce many converts to Christianity, as was hoped; rather, they introduced Western learning and some Christian ideas to young people who would later take leading roles in society.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, there were about 1,500 Protestant missionaries, including wives, working in 500 stations in almost all the provinces of China. About 500,000 people were connected in some way to Christianity, 80,000 being adult communicants. “But the missionaries were widely regarded – and feared – as the spearhead of Western penetration” (286). Suspicions and enmity had been brewing for years, particularly over the ways that some missionaries had “been less than discreet in making use of the privileges assured to them under the treaties; some had shown an insensitive disregard of Chinese feelings with regard to property and order” (287).

Again, Neill does not mention the fact that most of the hostility arose from the practice of Roman Catholic missionaries of arrogating to themselves the privileges of local officials and of claiming protection for their converts in civil cases. Nor were Protestants without fault, for some of them appealed too quickly to civil authority in local cases involving Christians, and even had occasionally called in their governments to protect their treaty rights.

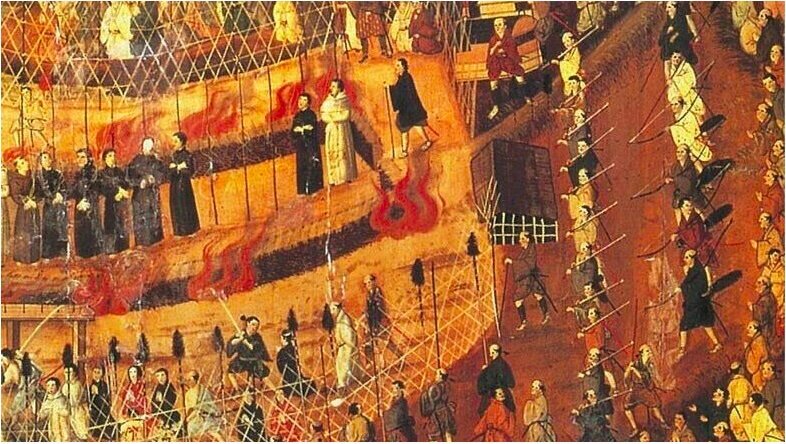

Long-simmering hostility final erupted in the summer of 1900, when, backed by the Empress Dowager, the so-called “Boxers” went on a rampage, killing both Chinese and foreign Christians. Roman Catholic Christians suffered most, and Protestant missionaries suffered as well, especially the CIM, since they lived in the interior. When it was all over, 188 missionaries had died, the largest number by far in Christian history. Though the CIM had suffered the most, Hudson Taylor decided to refuse compensation for these losses.

In the aftermath of the Boxer movement, in “Christian circles there was little resentment against China and the Chinese. The one thought of most of the missionaries who had lost everything was to get back as soon as possible to their chosen work and their beloved people. New societies entered the field; old societies greatly strengthened their forces. At the end of our period, there were no less than 5,462 Protestant missionaries in the field, including the 1,652 wives of missionaries” (288).

Furthermore, the years following 1900 “were years of exceptional openness to the Christian message,” with students asking the question, “How can China be regenerated?” (288). Many of those enrolled in Christian colleges were baptized, but few joined the church. “This rising Chinese Christianity had a somewhat exceptional character. It was little interested in the question of personal salvation. Not ‘how can I be saved?’ but ‘how can China live anew? – this was the burning question. . . . What they stood for was ‘the Christian movement in China.’ Ethically high-minded, socially conscious, ready for service, they had little awareness of the place of worship in the Christian life; they were more interested in the practical expression of Christian faith than in its inner development” (289).

The old regime was overthrown in 1911. Sun Yat-sen, who became President of the Republic of China, was representative of these younger, educated “Christians.” During the next twenty or thirty years, though a tiny minority, these Christian elites played a major role in the attempt to modernize China and make it strong again.

The End of an Era

When the World Missionary Conference convened in Edinburgh in 1910, with delegates from most of the missionary societies in attendance, optimism prevailed. This was the largest such gathering in Christian history, and they had good reasons for their high hopes for the future. As Neill points out:

· Though a few countries remained closed, “missionaries had been able to find a footing in every part of the known world.”

· “The back of pioneer work had been broken. Language had been learned and reduced to writing; all the main living languages of the world had by now received at least the New Testament.”

· “Tropical medicine had solved most of the problems of disease, and made possible the prolonged residence of the white man even in the most unfavorable climates.”

· “Every religion of the world had yielded some converts as a result of missionary preaching.”

· “No race of men had been found which was incapable of understanding the Gospel, though some were more ready to receive it than others.”

· “The missionary no longer stood alone; an increasing army of nationals stood ready to assist him.”

· “The younger Churches were beginning to produce leaders at least the quality of the missionary in intellectual gifts and spiritual stature.”

· “The Churches had become engaged, as never before, in the support of the missionary enterprise.”

· “Financial support had kept pace with the rapid expansion of the work.”

· “The universities of the West were producing a steady stream of men and women of the highest potential for missionary work.”

· “The influence of the Christian gospel was spreading far beyond the ranks of those who had actually accepted it.”

· “Intransigent opposition to the Gospel seemed in many countries, such as China and Japan, finally to have broken down” (333).

Thus, Neill concludes that the slogan, “the evangelization of the world in this generation” was not a pipe dream, but a realistic concept. Its proponents were not saying that everyone would be converted, but only that each non-Christian would have had an opportunity to hear the saving message of Christ.

Further, “the slogan was based on an unexceptional theological principle – that each generation of Christians bears responsibility for the contemporary generation of non-Christians in the world, and that it is the business of each such generation of Christians” to preach the gospel to every creature.

Not all “the dreams of Edinburgh 1910 have been fulfilled. . . . But they were right to rejoice” when looking back over what K.S. Latourette later called “The Great Century” in Christian missions.

Chapter 11: Rome, the Orthodox, and the World, 1815-1914

As the title indicates, this chapter covers “The Great Century of Missions” with a narrative of the remarkable expansion of both Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox missionary achievements. For both groups, this period witnessed a veritable explosion of energy, along with greater organization, especially among Roman Catholics.

These advances were spearheaded by some truly outstanding, even heroic, individuals, like Cardinal Lavigerie, Archbishop of Algiers (1825–1892); John Veniaminov (1797–1879), who worked in Russia’s Far Eastern regions, finally becoming Metropolitan of Moscow; and Nikolai, missionary to Japan from 1861 to 1912. These men evinced great courage; learned the language and culture of the people whom they served; labored incessantly into old age; and left behind strong churches.

The weaknesses of Roman Catholic missions resembled those of their history: A strong reliance on European power and prestige; baptisms without careful teaching or evidence of true conversion; intense efforts to draw away adherents of other denominations, including Protestants and members of Eastern churches; and a top-down approach that targeted local elites and rulers.

Once again, I will concentrate on China, where, despite great danger, Roman Catholic missionaries had carried on in secret, being cared for by Chinese Christians as they move from place to place.

When the treaties gave certain rights to Christians and foreign missionaries, Roman Catholic missionaries pressed these rights to the farthest extreme, even going beyond treaty stipulations. With France’s strong backing, they carried French passports, regardless of their national origin; supported Roman Catholic converts in civil and even criminal cases even when “it was not always easy to be sure whether it was for his faith that the convert was being persecuted, or for some other and much more legitimate reason. Missionaries tended to interfere in lawsuits, and to use their influence with magistrates and others in favour of the Christians. . . . It can hardly be doubted that the Roman Catholic method in China opened the door wide to those who came in for purely mercenary motives. . . . A firm link was being forged between imperialistic penetration and the preaching of the Gospel” (345).

Building on their longer tradition of work in China, Roman Catholics grew more rapidly than did the Protestants. “But nemesis was preparing: if unsatisfactory methods are adopted, sooner or later a heavy price will have to be paid for their adoption” (346). When the Boxer madness erupted, Chinese Roman Catholics suffered the most as being too closely associated with foreign imperialism.

After the Boxer rebellion, however, as with the Protestants, so the Roman Catholics were “able to profit from the new spirit of openness in China, new Orders and societies entered, the work was reorganized and extended, and the number of (Roman Catholic) Christian grew more rapidly than ever before” (347).

The problem now, however, was the absence of Chinese bishops. With one major exception, the missionaries were very conservative, and felt that they should retain leadership of the churches. That exception was Vincent Lebbe, who campaigned long and hard for total identification of the missionary with the people he had come to serve and who, like Hudson Taylor, believed that it was better to suffer with the Chinese Christians than to rely on foreign gunboats for protection.

Chapter 12: From Mission to Church

Professor Neill died in 1984, twenty years after this book first appeared. Before his death, he gave instructions for the revision of the volume in the light of more recent events. Professor Owen Chadwick, series editor of Pelican (now Penguin) Books and author of the volume on The Church in the Cold War, made the revision, especially of the last two chapters.

This chapter traces two movements around the Christian world: The first, from the leadership, or even dominance, of missionary societies over the local churches that they had planted, and the second, from separate denominations to national, regional, and then international organizations, or councils, of denominations.

The author writes as an insider, since he was a bishop in the Anglican communion and then in the Church of South India.

As a result of the 1920 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh, national committees were set up in many countries around the world, particularly as the result of a tour of Asia by Dr. John Mott in 1912–1913.

Toward Independence

The movement towards self-government by local churches gained momentum throughout the first part of the twentieth century, as nationalism, the debacle of World War I, and the emergence of strong indigenous leaders combined to demand greater independence from foreign missionaries. Sadly, too many missionaries still believed that the newer churches were not mature enough to govern themselves. Furthermore, financial control remained in the hands of foreigners, especially with regard to institutions such as schools and hospitals.

Sometimes it took the “disappearance” of missionaries to make native leadership both necessary and possible. This happened in China when foreign consuls ordered their nationals to evacuate their posts during the Anti-Christian Movement and general chaos of 1926–1927, and again when all the missionaries were expelled after 1950.

Organizational autonomy is one thing; indigenization of theology, worship, and ethics is another. Neill very wisely comments on the complexity of this difficult transition:

Reluctance comes primarily from the converts themselves, and from their reluctance to have anything to do with the world from which they have emerged. Only in rare cases does the convert regard his former religion as a preparation for the new. The old world was a world of evil in which he was imprisoned, and from which he was delivered by the power of Christ. The last thing that he wishes is to turn back in any way to be associated with that which to him is evil through and through. And, after all, he is the only man who knows; he has lived in that world, and knows better than anyone else its lights and shadows. If his reaction to that world is wholly negative, who has the right to blame him? (397-398)

Toward Christian Unity

Neill next provides us with a fine description of the process by which different ecclesial groups created national and then trans-national organizations. That is, he describes the growth of the Ecumenical Movement.

In a few cases, like Japan, China, and India, denominations merged – or were forced to merge by the government – into one union. In others, common efforts, especially in Bible translation, brought about new, though sometimes informal, associations.

Another impetus was the desire of local Christians to be freed from the confusion and competition of a multiplicity of mission societies and denominations. Why couldn’t they all just be “Christians”? Furthermore, as they matured, the newer churches sought liberation from control by foreign missions and church organizations with headquarters in the West. These are certainly understandable aspirations.

As I have noted before, Neill firmly believes that organizational unity must be pursued. His view of the “Church” is of an organization headed by a bishop in communion with other bishops. Congregationalists and, to a lesser degree, Presbyterians, would see things differently. Even they, however, often band together in large “networks,” as with the “house” churches in China, though Neill does not discuss this in the present chapter.

In general, large conventions became “councils” with stronger or weaker ties of union. Neill sees all this as positive, even necessary. For theological reasons, evangelicals have often resisted this approach. After Neill had died, Billy Graham and John Stott convened the Lausanne Congress on Evangelism in 1974. Its continuation committees and periodic meetings have created an evangelical counterpart to the World Council of Churches.

For this reader, the identification of “Church” with “denomination” lacks biblical warrant, so this chapter, though extremely helpful as an historical analysis, raises as many questions as it answers.

Chapter 13: Yesterday and Today, 1914 and After

This final chapter, like those that preceded it, contains so much important detail, such elegant writing, and so many brilliant analyses and insights, that one is tempted to quote, not just whole paragraphs, but entire pages. In a review and summary that is already too long, that would not do. I can only try to make this section shorter than others, select a few excerpts, especially about China, and wholeheartedly commend the entire volume as essential reading for any student of missions or even of world history.

Nationalism, and a general desire to be free from Western domination, had been brewing for a long time even before World War I. Then, the “European nations, with their loud-voiced claims to a monopoly of Christianity and civilization, had rushed blindly and confusedly into a civil war which was to leave them economically impoverished and without a shred of virtue” (415). After that, the “Russian Revolution of 1917 was a new and perplexing factor in the situation. A great new anti-Christian force had been let loose upon the world, a force with which for the future the Churches would have to reckon” (416).

“The natural consequence of all this was the awakening of the ideals and passions of nationalism among the peoples of Asia and Africa. [Nationalism can have its noble aspects,] but this can easily slip over into a narrow and arrogant intolerance, and a contempt for the members of other and less favoured nations. If the state is deified and becomes the final and unquestioned authority in all the areas of man’s life, then the way is opened to idolatry and blasphemy against God” (417).

Meanwhile, “the mind and temper of the Christian churches was becoming afflicted by a new kind of uncertainty” (417). Liberal theology began to question the core tenets of the faith. This led quickly into a repudiation of the fundamental premises of Christian missions, that Jesus is the only Savior and that his message must be preached to all peoples so that they can be saved.

In spite of all this, thousands of Christians continued to offer themselves for service as cross-cultural missionaries. The authors note five facts: 1. Most new missionaries (at the time of revision, 1986) were from the United States. 2. The growth came mostly from the rise and expansion of non-denominational societies. 3. Pentecostal and charismatic churches and their missions assumed an increasingly prominent place in several parts of the world. 4. The historic churches of Europe “were making far less than a proportionate contribution to the work of Christian witness in the world,” mostly because of the ravages of World War II. 5. After independence from colonial rule, the number of missionaries in India and Africa fell drastically.

As a result, “for all the elements of disturbance, conflict, and chaos that have been let loose upon the world since 1914, and in spite of the extermination of Christian work through communist nations in certain areas such as Central Asia, missions and Churches made unexampled progress in the period now under review. . . . It is in this period that we discern the beginnings of the landslide through which in many parts of the world hundreds turned into thousands and thousands into millions” (424-425).

From our perspective, those millions have turned into hundreds of millions, including the almost incredible explosion of Christian in China since this revised edition was published.

Turning to China in this period, however, we see, first, the chaos following the revolution of 1911; the growth of all forms of Christianity during the brief Nanjing Decade of the Kuomintang (Guomindang) under Chiang Kai-shek (1927–1937); the horrendous suffering inflicted by the Japanese invasion and occupation of much of China (1937–1945), which, surprisingly, led to new advances of the gospel into hitherto under-served areas; a brief respite after the conclusion of the war; and then an entirely new situation after the communists gained power in 1949.

After a short time of relative freedom, all but handful of missionaries had been expelled by 1953. From 1950 onwards, the state took control of the church. At this point, our authors opine that many Christians were happy to see the foreigners kicked out and the church come entirely under indigenous leadership. That was no doubt true, for henceforth Chinese Christians stood entirely on their own, untrammeled by Western control.

On the other hand, increasing suppression, then oppression, by the government meant the loss of schools, hospitals, church buildings, and then even pastors, the low point coming during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). “In 1981 there was evidence of rapid Christian growth among the young, but the whole episode of 1949–1980 was a Christian disaster of the first magnitude” (431).

At that time, no one on the outside could know that, deep underground, in prison cells and secret home meetings, Christians had continued to meet and to share their faith. During the 1980s and afterwards, up to the present, Protestant Christianity has continued to grow at a rate unprecedented in Christian history.

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong and Taiwan, missionaries were free to work, and they did, strengthening local churches and aiding in evangelism up to the present time. The new reality, however, was local control by Chinese Christians, with foreigners serving as assistants or as pioneer evangelists.

How I wish I could follow the thrilling story of the phenomenal growth of the Christian faith in India, Africa, and Latin America, brilliantly recorded here!

Conclusion

Not surprisingly, the book ends with a powerful conclusion.

“In the twentieth century, for the first time, there was in the world a universal religion – the Christian religion. . . . In country after country . . . it took root, not as a foreign import, but as the Church of the countries in which it dwells” (473). Though the term is not used, this was the period when “World Christianity” fully came into being as the major development in Christian history and, perhaps, of all human history.

“At a time when Churches were declining, at least in numbers, in many of their historic European homes, the statistics of Christian expansion were still extraordinary” (473). These final pages trace this phenomenal growth around the world, in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe. It is true that Christianity faces strong opposition in the Muslim world, some Buddhist countries, and communist countries like China.

In addition, “the Churches in Asia were engaged in a holding action, not an advance. The old religions of Asia pulled themselves together, recovered their spiritual inheritance, realized that they had things to offer their world. They seemed to be making themselves and their adherents even more impervious to the Christian Gospel” (476). One thinks of Buddhist countries like Thailand, Burma, and Taiwan, for example, and, especially recently, India. But even in India the church continued to rescue hungry souls from darkness.

Looking back over the broad sweep of history, the authors note that in the unbroken darkness of the tenth century in Western Europe, it must have seemed most unlikely that the Church would ever find the way to greatness. . . . But what followed was . . . the first great renaissance of Europe, with Anselm as its principal thinker, and Norman architecture as its massive and memorable outward expression.

The cool and rational eighteenth century was hardly a promising seed-bed for Christian growth; but out of it came a greater outburst of Christian missionary enterprise than had been seen in all the centuries before. There is no reason to suppose that it cannot be so today. But such renewals do not come automatically; they come only as the fruit of deliberate penitence, self-dedication, and hope (477).

Even as this edition was being sent to press, a new age of missionary expansion had begun, as countries like South Korea, India, and Brazil thrust forth workers in harvest fields around the world.

And yet; and yet –

“A third of the people in the world, perhaps, have not yet heard the name of Jesus Christ, and another third, perhaps, have never heard the Gospel presented in such a way as both to be intelligible and to make a claim on their person lives. There is plenty still to be done” (478).

On the other hand, and despite all the faults and failings of previous generations of Christians, “the Church is there today, the Body of Christ in every land, the great miracle of history, in which the living God himself through his Holy Spirit is pleased to dwell” (478).

Amen!

[1]. A short biography of Taylor can be found at Taylor, James Hudson | BDCC (bdcconline.net).

[2]. See a brief biography of Richard, go to Richard, Timothy | BDCC (bdcconline.net).